Originally published in The Morgan Horse Magazine, March 2022. Copyright protected, all rights reserved, shared with permission.

Find out more about our breed magazine here!

Promoting the Morgan Horse and Celebrating Its Diversity

Originally published in The Morgan Horse Magazine, March 2022. Copyright protected, all rights reserved, shared with permission.

Find out more about our breed magazine here!

Two years back, I wrote about a green ribbon cracking the glass ceiling, when my three year old pony-sized Morgan mare Spirit’s Celeste took sixth place in a massive Open In-Hand class at Dressage At Devon. The thing about cracks is they start to sag, and widen, and at some point, a clever little fish fry could wiggle itself through, into the big pond.

The thing about being the little fish in the big pond is that you can stay hidden, slyly slipping from shadows and under leaves, watching the bigger fish, a little bit in fear because they are large and can be scary, but also in wonder and learning. Watching and staying mostly unseen, you can learn the patterns, the routines and rituals the bigger fish use throughout their lives in order to become creatures of their size. Little fish can grow, and instead of the minnow scales we believe we carry, we could instead develop bright colors, or fancy fins. Taking the time to be an observant little fish means that when we’ve grown up a bit and started to get a little bolder, we might be more ready to swim freely in the big pond.

Yes, I do love metaphors.

My first showing with Dressage at Devon was in 2018, with my little stallion Primal Thunder. I had not shown since I was a young teenager and only then in schooling or fair shows, and he was fresh off a summer of breeding and only light work. We were greener than grass and the smallest fish in that big, intimidating pond. Our high score of 68.4% meant nothing to me, not like it should, only that if I’d taken a test in school I’d have received a D+.

The reason I always return to this particular show is that I was this green unknown entity, asking the show staff oodles of questions and making mistakes and everything – but they were all kind to me. I felt encouraged, supported, and my stud pony’s good disposition and cute appearance attracted compliments enough that I felt maybe, just maybe, my idea of breeding Morgans for sport, wasn’t all that crazy.

2024 was my sixth showing at Dressage at Devon. Sadly we all skipped 2020 for the plague year, but I have gone every year since 2018. I might be a weird long finned betta fish in a pool of massive carps, but I think we are learning “the moves.”

I brought the best of my matrilineal breeding this show, descended from Triplesweet Trinity, a mare I bought from a lesson program who has heartily surpassed my highest expectations for her as a broodmare. This lineup included Spirit’s Celeste, her daughter by my stallion Primal Thunder, Starberry Solstice, her son by CM Sunday Kode from Canada, and Starberry Shamrock, the first son of Spirit’s Celeste by Clear Creek Zeus, who was rescued from a meat truck (I’ll blog about his story later). A weird sounding grouping on the sire sides, but in my head, it worked. A nice mix of blood highlighted by Courage of Equinox, Merriehill Chicagoan, Beamington, UVM Promise, Trophy, Bennfield’s Ace, and Chasley Superman genotypically, that to me, phenotypically turned out nice sport pony and sport horse type for the breed.

Dressage at Devon’s Breed Division is primarily showing horses in hand, young stock and breeding adults, but it also includes a set of under saddle classes called Materiale. All of these are to assess conformation, motion, trainability, etc, to understand if a horse is suitable for a future in dressage and similar sports. Of course, I paraphrase, but if you are interested in a complete description of the aims of the classes and how they are judged, I urge you to check out http://www.dressageatdevon.org and http://www.usdf.org. Some of you might know that I do not generally begin riding my horses until they are four or older, as their spines are still forming until about age six, and I would rather have a horse who has a long productive life that began a year or so late than a horse who retires before twenty but started at three. What this means for my sport horse program, though, is that I am behind for the Materiale. Materiale classes are for ages three, four, and five. Originally my intent had been to show Miss Celeste at four in Materiale, but the vet advised to wait a year on bitting under saddle due to how her teeth were shedding and developing, so she carried her first foal and had some ground work but mostly got to take her four year old year to grow herself and her baby. Her colt was born on St Patrick’s Day and he’s perfect. To me anyhow.

Materiale is a new division for me. As a child I rode hunter flat classes so the concept of a walk trot canter class is not foreign to me, but I had still not ever ridden, as an adult, in a horse show of any kind much less an A-rated show in the oldest fairgrounds in the country. Greener than grass, people. For real. But, we did our best. I started Celeste under saddle in the end of May. It’s true what they say about riding starts from the ground, and if you can do it on the ground, you can probably get it done in the tack too – my girl was ready for the saddle work to start, and learned her cues quickly. Her fitness was a bit less than was desired, as she’d just delivered her first baby, but with our chiropractor’s adjustments and our vet’s diet recommendations, the endurance and muscle building workouts got her physically about where she needed to be.

We arrived at Devon Fairgrounds on Monday, middle of the day. Evening, they’d set aside time just for the Materiale horses and riders to spend time in the two rings, getting used to the lights and the flowers and the like. It was almost dark when we saddled up and headed out, two green little fishes in the big blue rings. Celeste, just under fifty rides into her riding career, did not put a foot wrong. She looked, sure, she counter bent to examine things or when something sounded weird, she put her head up in surprise at things, she even did a slight kick up of her heels when she needed to do a full body shake so I’d get off and let her shake without me in the saddle. That’s it. We did a brief walk-trot-canter both ways in Wheeler, and a nice big walk both ways in the Dixon Oval. Seventeen and eighteen hand warmbloods passed us and Celeste just focused on me, her surroundings, and her job. She hadn’t been off property since we were last at Devon, in 2022, and she’s never been ridden in… a proper arena. Our riding space at home is clay soil, sometimes with grass in it, that’s sometimes too hard to ride at more than a walk, or a slanted uneven grass hillside. This beautiful level footing was soft and predictable and I could feel Celeste enjoying it on her feet.

I’m not sure I slept that night. Our ride wasn’t until midday. As I am not an early morning person, this suited me fine, and let me take the morning to warm up my three horses with nice walks around the fair grounds and get myself dressed and ready without feeling rushed. Our first in-hand class was scheduled to immediately follow the Materiale ride, so I wanted to be sure my colts were stretched and clean and set, and that my amazing groom would be ready to help me quickly tidy up Celeste between her ride and her run. Quick shout out to Noelle for being the best right-hand-woman, jennie-on-the-spot, self motivated and sunny show groom!

I was a bit freaked. It’s not every day that you take your first ride in a show ring since you were a tiny pre-teenage human, and for it to be at an A-rated show like Dressage at Devon… I tried not to think about the level of anxiety I should be experiencing so it wouldn’t hit me. Celeste looked stunning, mane in perfect plaits, coat buffed to a healthy shine, tack clean and gleaming. I mounted up.

Not one but four of the riders I was in the class with complimented me on my adorable pony in the warmup ring, with bright, friendly smiles. I should add, the rest of the class averaged 17hh, and Celeste had been measured the day before for her temporary pony card (permanent card at eight and she is five so is measured every season) at 138 cm, or 13.2hh. A pair of trainers I have known since I began showing at Dressage at Devon was at the rail, and as I passed, they shared encouraging words and reminded me to breathe and sit back. I am so grateful for them. They got my head back in the game right before we began the class.

Celeste, in her fiftieth time under saddle, took to the arena boldly, forward but listening, and she did everything I asked. Including, to my embarrassment, picking up the incorrect lead going right, but I am certain it is because I was not balanced from my own nerves. My beloved pony took care of me, and we got the lead fixed. As the littlest horse, I made sure to put us on the inside when passing other horses, and circled in front of the judges to prove her flexibility. We made it. I did not fall off. She did not freak out. She was a star. We scored 69.4% and took home a ribbon.

Photo by Jess Casino Photography

Feb, 2023 (somehow forgot to publish…)

I’m still recovering from a broken leg I sustained in 2021. I did a foolish thing, but I imagine many of you horse people out there would understand… I got in the way of a horse kick, aimed at another horse, that likely would have permanently crippled the other horse. I didn’t exactly mean to, but the consequences of trying to settle unhappy horses and prevent their damage… well, I’m glad it was me not the mare, because I can heal a lot more easily, as three months in a wheelchair won’t exactly drive me out of my brain. At least not entirely.

At some point, we’ve set up for the jump, we’ve adjusted the stride, we’ve found the distance, we’ve steered for the center and looked for the next jump – when we hit the base of the jump, whether we are ready or not, whether we are correct or not, at this point we just need to prepare for take off and let the horse carry us to the other side.

It’s been a long hard recovery but, I am ready to get back into everything,

Continually I have thought to myself, gee, I should blog about that thing I just was discussing, or thinking about…

…and then have gotten waylaid by the world and left this to molder in the ditch,

I’ve had a busy couple of years – healing from a broken leg, refocusing my program, buying and selling, and continuing to write for The Morgan Horse magazine on occasion. I have some articles to share now too.

For whatever the cause, I am returning now.

I look forward to continuing the journey.

Me and Spirit’s Celeste, Photo by Stacy Lynne Equine Photography, 2024

Everything we say and do in this world is subject to the jury of public opinion.

It is hard not to be, given how we present ourselves to the world through social media outlets of the modern day.

The trouble begins when we don’t have the entire story panned out for us in a readily digestible format, we sometimes loathe or romanticize things that do not deserve either.

For horses this often means, “oh my horse has ancestor X; I love my horse, therefore ancestor X must have been great,” and we find a photo in an archive someplace or a long lost show record that validates our opinion. The problem is we then make our opinion out, publically, to the world, as if it is FACT. It is OK to like ancestor X, and if you want to seek out someone to breed to who is also related to ancestor X in order to keep that bloodline in your own herd, by all means help yourself have fun.

In our eagerness to make what we like seem more valid to our peers, we state things that are opinion as if they are fact, and then peers often accept it as fact and not as opinion, especially if they do not necessarily have as much insight as another in the topic – which creates a fallacy on multiple levels.

Say for example ancestor X looks just like your horse, and you look him up and find that ancestor X also won a world championship title in the discipline of your choosing. This would validate your feelings that ancestor X is a superior choice, full stop. What if though ancestor X was the only entry in the class? What if ancestor X, in fact. went to no other horse shows and was actually not a great example for the discipline but just got very lucky?

But we often don’t do that extra digging to see the entire picture from all sides, because our opinion has been validated by social media, and therefore we see it as truth.

This happens a lot in horse breeding.

Let’s think about a different example – let’s call this one horse Y. Horse Yis a beautiful specimen. He is well conformed, he has type for his breed, he is a desirable size and a desirable color, and he competes at a level that implies a certain mastery of his skill. Suppose horse Y retires and becomes a breeding stallion, because with his beautiful show record an equally beautiful self he would be a desirable father for one’s herd. Suppose horse Y has 100 viable offspring from a number of different owners and out of a number of differently blooded mares. Even with this level of research not being the deepest one could dig, one could assume this is a desirable and popular and successful stud.

Suppose horse Y was doing all of the breeding starting about 40 years ago. If you were a desirable popular and successful stud, it would be a safe assumption that his bloodline would still be readily present in many horses in his discipline.

But what if there weren’t?

Then interest in ancestor X and interest in horse Y would cause the interested party to potentially make the same sort of claim: “people are shortsighted,” and/or, “people are stupid,” and/or, “people don’t know what they’re missing,” and/or “we’ve got to save is this rare/endangered/valuable/old/historic individual bloodline.”

I believe sometimes this is the right call. Sometimes ancestor X and horse Y proved to be more valuable than people initially had anticipated. I believe though that this is the exception, not the rule.

Ancestor X might have produced the horse the interested person currently has by some means or other and maybe the horse that person has is wonderful, but what else did ancestor X produce? Watch those horses’ produce, do they have show records? Or have they dead ended and not continue to breed on for reasons unknown?

Stallion Y might have produced 100 offspring, but how many of those offspring produced anything? Let’s say a successful breeding stallion who is desirable in the breed produces maybe 50% that continue to breed on – because we know not all horses are bred because the primary purpose of horses is to be a riding companion or what have you – but let’s say it’s maybe 50%. What if stallion Y only has 10% of his offspring who have ever produced a grandfoal? And what if of those grandfoals, only 10% produced any great-grandfoals? We can trace these blood patterns, and we can see where people have purposefully chosen not to continue to breed a certain line. Yes, I will say there’s got to be a couple cases where people have been shortsighted, but I believe it is much more frequently the case that an individuals bloodline dies out because the individual does not produce desirable offspring, no matter how much we want to believe that of course they should have created wonderful offspring, because one horse down the line is wonderful.

We forget so much that a lot of factors influence what makes a good horse. It’s not just one ancestor or one parent or one person, it is all of these things. The genetics, the random chance that happens with recombination of chromosomes, the personality of the mare raising the foal, the handling of the foal by the breeder and trainer and owner and on down the line.

The lesson here, I really hope, is, Rarity Does Not Equate Value.

Performance, Conformation, Type, Personality, Get, Success of Get, is where value is accrued.

Last year, when recovering from a badly broken leg, I decided one of the things I would do to cheer myself and think to the future would be to learn about Dressage Freestyle. I see freestyle at the Grand Prix level as the pinacle of the discipline, a true mastery of the movements and subtleties that are built over time and through the levels. Freestyle is also the most relatable of tests in dressage, as it is done to music. Music is a universal language for people, and while taste can vary widely, we all understand and appreciate it. Understandably, it is most of what we see televised for Olympic Dressage, which also builds it in the mind of the public as that high point to achieve in the sport.

I believe I am not alone when I say that sometimes, when listening to music I truly enjoy, I envision in my head riding to the music. Particularly after the beautiful WEG 2006 Freestyle Dressage Final test ridden by Andreas Helgstrand on Blue Hors Matine was redubbed and shared widely on social media, I think a much greater number of people, equestrians and not, could imagine a horse dancing to their favorite music.

To me now, after many hours elevating my healing limb in the company of the United States Dressage Federation website, various YouTube personalities, and dressage books, watching that video of Blue Hors Matine’s test with the wrong music is like watching an episode of Bad Lip Reading. It is entertaining, it is admirable, but it loses a lot in translation.

It is also notable that I am a lifelong musician. I have played the cello since age four, had instruction as well in singing, piano, musical theory, and composition, and still play several instruments. I also studied ballet for many years as a child. The relationship between the physical movements of the dancer and the musical movements has always been paramount to how I understand dance, and music created for dancing. When I was told that Anky van Grunsven hires a composer to write music for her horses, my head said to me, but of course!

We cannot all employ a composer and orchestra to write music tailored to the specificities of our horses’ strides, but we can find it. For each freestyle, music ought to be chosen for each gait, walk trot and canter, based in the hoof beats’ tempo and the music’s bests per minute. Google is a great resource for finding the right beats for your beast! What makes a test like Blue Hors Matine’s work so ideally for the watching audience is what the announcer says, the horse is dancing!

The je ne sais quoi of freestyle is to find the music that elevates your horse to the level of apparent dancer. Someone watching from the ground should feel moved by the performance, like a ballerina in Swan Lake. The connection between the horse and the music should be indisputable, and it should move you.

Sometimes, what moves your horse and makes him look stunning, is not to your own taste. Sometimes what shapes the movement and the visual of our horses is unexpected. I believe though, the very best freestyle music should move horse and rider. A rider who unconsciously moves along to the beat – even imperceptibly – translates that excitement, energy, or elation to their mount. And vice versa. This is a dance, all riding is a dance really, and both partners should feel moved by the movements before they lay out their movements.

Sometime, when I’m more than just two years into my dressage riding, I’ll find that song with my horse, and we shall dance.

The Original YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/zKQgTiqhPbw

This is the very first article I wrote for The Morgan Horse Magazine! It is a privilege to be a writer for this publication, helping to show our breed in every facet that makes it magnificent.

Originally published in The Morgan Horse Magazine, November/December 2021. Copyright protected, all rights reserved, shared with permission.

Find out more about our breed magazine here!

https://www.morganhorse.com/magazine/subscribe/

My next article is coming up for The Morgan Horse Magazine!

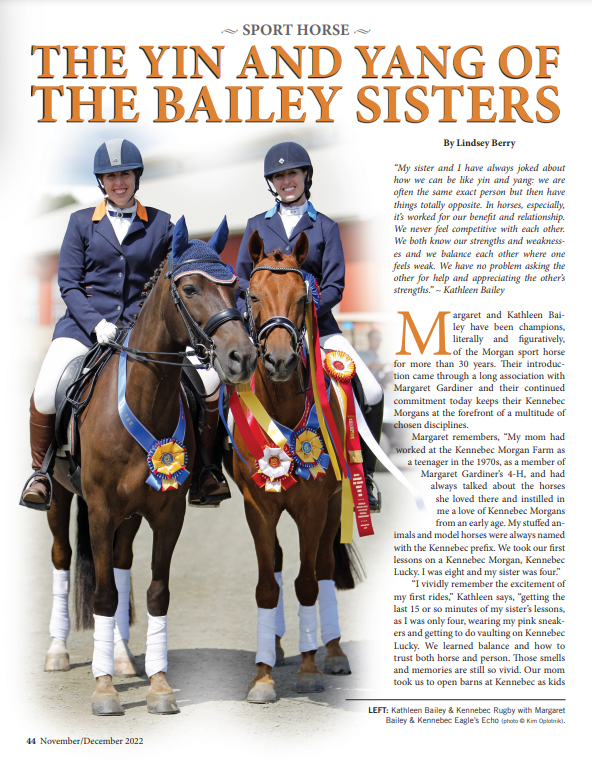

Get the in-depth scoop on Margaret and Kathleen Bailey, their passion for Kennebec Morgans, and how they prove the true versatility inherent in our breed!

To check out the full scoop and the rest of the Morgan news, subscribe here! https://www.morganhorse.com/magazine/subscribe/